Introduction

The vajra (Sanskrit) or rdo-rje (Tibetan) is a mythical weapon used as a ritual object in Buddhist ceremonies and a key symbol of Vajrayāna, one of the three major Buddhist traditions. Typically fashioned out of bronze or brass, the vajra is comprised of a spherical central section. Two lotus blooms are fashioned on either pole of this central section, with a set of five or nine prongs arcing from each one that meet at points equidistant from the centre. For more examples on the different types of vajras, visit the Himalayan Art Resources online archive.

Origins of the Vajra

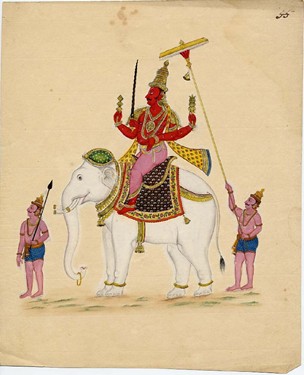

The earliest mention of the vajra is in the Rigveda, one of the four Vedas or ancient Indian religious texts. Composed around 1200-1500 BC, the Rigveda depicts the vajra as the weapon of choice for Indra, the Vedic deity who rules over lightning, thunder, rains and river flows. He used the vajra to conduct the forces of thunder and lightning, bringing about destructive storms upon his enemies or much-needed rainfall upon parched crops. Wielded by the King of the Gods, the vajra is deemed in the Indian mythology canon to be the most powerful of all weapons on earth. d’Oldenburg describes the vajra as the “best weapon”, a “weapon par excellence”, best suited for a devata, or deity. Parallels have been drawn between Indra’s iconography with that of other thunderbolt-bearing sky-gods: the Greek god Zeus and the Roman god Jupiter both brandish lightning bolts, and The Norse god Thor possesses a hammer named Mjölnir, which literally means “lightning”. For more information about the cross-cultural appearance of the vajra, visit the YouTube link listed below.

Symbolism in Buddhism

More than just a mythological weapon, however, the vajra is replete with symbolic meaning. Literally translated into “diamond” or “thunderbolt”, a vajra symbolises the blinding brilliance and indestructible hardness of a diamond, as well as the unparalleled destructive capabilities of a thunderbolt. In the Vajrayāna tradition, it is a symbol of the indestructible, immutable and ultimate goal of Vajrayāna: the attainment of the enlightened state of Buddhahood. The attainment of Buddhahood in Vajrayāna is deemed by many Buddhist practitioners as superior to that of the Mahayāna tradition, because the former is achieved through much more potent means and is therefore more powerful and permanent. While Buddhahood is achieved through multiple lifetimes in the Mahayāna tradition, it can be achieved in a single lifetime through tantric practices, the main methodology used in the Vajrayāna tradition.

Ritual Use and Symbolism

The vajra is almost always used in conjunction with a ritual bell called a ghaṇṭā (Sanskrit) or tribu (Tibetan). The sound of the ghaṇṭā was believed to ward evil spirits off. The vajra symbolises the male aspect, compassion and upaya, or skillful means, while the ghaṇṭā symbolises the female aspect, emptiness and wisdom. During Buddhist ceremonies, the vajra is typically held in the right hand, facing down, while the ghaṇṭā is held in the left, facing up. The hands are often moved in specific symbolic gestures, or mudras, while the monk chants. For more information about the specific mudras and chants used with the vajra, please visit the external YouTube links listed below.

It is not uncommon for the hands to be held at the chest with the wrists crossed, denoting the union of the vajra and ghaṇṭā, and by extension the inseparability of the “qualities and requisites for enlightenment” (Linrothe 2014, 10) they represent. This is alluded to in one of Saraha’s couplets from Tantric Treasures: Three Collections of Mystical Verse from Buddhist India. He writes:

Rejecting compassion,

Tantric Treasures: Three Collections of Mystical Verse (Jackson 2004, 61)

stuck in emptiness,

you will not gain

the utmost path

Nurturing compassion

all by itself

you’re stuck in rebirth,

and will not win freedom.

In the translator’s note, Jackson writes that both compassion and emptiness, which the vajra and ghaṇṭā respectively represent, are “necessary for attaining enlightenment, and the practice of one to the exclusion of the other will result in spiritual frustration.” (Jackson 2004, 61)

Not only are the vajra and ghaṇṭā symbolic of these qualities necessary for enlightenment, but their pairing also symbolises the Tantric belief in non-duality. The principle of non-duality is encoded in the Heart Sutra, which Thích Nhất Hạnh explains in his commentary on it by explaining the “interbeing” (Nhất Hạnh 1988, 3) of things – that things only exist in relation to other things and are “empty of a separate independent existence” (Nhất Hạnh 1988, 10), and therefore “We are not separate. We are inextricably interrelated.” (Nhất Hạnh 1988, 37) Linrothe writes, “These two ritual implements together signify the most important qualities and requisites for enlightenment according to Esoteric Buddhist understanding (…) their union constituting the breakage of the bonds of binary thinking or ordinary consciousness.” (Linrothe 2014, 10)

Together, the vajra and ghaṇṭā thus symbolise the inseparable qualities needed for enlightenment, and the principle of non-duality at large. For more examples on the different types of vajras and ghaṇṭās, visit the Himalayan Art Resources online archive.

Vajra as a Prefix

Prefixing Buddhist terms by “vajra-” is also very common in order to add on connotations of the strength and immutability of the vajra to the root word. “Vajrayāna” is one such example. For a full list of the vajra- prefixed terms, refer to The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism.

Vajrasattva

The Vajrasattva, a deity from Vajrayāna Buddhism. Sattva means “being”, so Vajrasattva means “vajra-being”, and therefore representative of what the vajra represents. According to Linrothe, the Vajrasattva is “a coded abstraction, a personification of ideas that are exclusive to Esoteric Buddhism” (Linrothe 2014, 7). Iconographically, the Vajrasattva is depicted holding the vajra in his right hand, to his heart. The Vajrasattva is central to tantric visualisation practices. For more information about this, refer to the Buddhist Weekly article on Vajrasattva.

Vajrapāni

Another significant vajra- deity is that of Vajrapāni, or “holder of the vajra”, who is an important bodhisattva in both Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions. Vajrapāni protects mantras and those who recite them, and manifests in both peaceful and wrathful forms. The peaceful Vajrapāni does not hold the vajra in a specific position, but the wrathful Vajrapāni holds the vajra over his head, as if about to strike down those who have incurred his wrath.

Other Vajra Iconography

The vajra is often depicted in all forms of Buddhist art, ranging from thangkas (traditional Tibetan paintings) to statues to bas reliefs. In fact, the vajra is such a central representation of Vajrayāna and Buddhism that it has been adopted by Buddhist nations as a national symbol: the incorporation of a double vajra into Bhutan’s national emblem is testimony to the importance of the vajra. Viśvavajra, the Sanskrit word for the double vajra, means the all-pervading, universal and omnipresent vajra. It is postulated as the foundation of the universe, and hence represents absolute stability.

References

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Vajra.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 19 Sept. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/topic/vajra. [A succinct summary of the usage and symbolism of the vajra.]

Jackson, Roger R., et al. Tantric Treasures: Three Collections of Mystical Verse from Buddhist India. Oxford University Press, 2004. [

Hạnh Nhất, Thích. The Heart of Understanding: Commentaries on the Prajnaparamita Sutra. Edited by Peter Levitt, Parallax Press, 1988. [The Prajnaparamita Sutra, or Heart Sutra, is one of the most popular sutras in the Mahāyāna tradition, upon which the Vajrayāna tradition is based. Thích Hạnh Nhất explains the principles of interbeing and emptiness in his commentary simply and elegantly.]

Linrothe, Rob. “Mirror Image: Deity and Donor as Vajrasattva.” History of Religions, vol. 54, no. 1, 2014, pp. 5–33., doi:10.1086/676515. [A journal article on the iconography of the Vajrasattva.]

Further Readings

Powers, John. Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Revised Edition. Snow Lion Publications, 2007. [An overview on Buddhist traditions at large, including the origins, principles and practices of the Vajrayāna tradition. This reading would be useful in helping one locate the Vajrayāna tradition in the Buddhist canon.]

“Vajrasattva, the Great Purifyer, among the Most Powerful and Profound Healing and Purifications Techniques in Vajrayana Buddhism.” Buddha Weekly: Buddhist Practices, Mindfulness, Meditation, 26 Oct. 2018, https://buddhaweekly.com/vajrasattva-great-purifyer-among-powerful-profound-healing-purifications-techniques-vajrayana-buddhism/. [A more in-depth explanation of the symbolism of the Vajrasattva, as well as the visualisation practices related to Vajrasattva specific to the tantric Buddhist tradition.]

Buswell, Robert E., et al. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press, 2014. [An extensive dictionary of vajra- terms, as well as many other Buddhist terms.]

External Links

“Ritual Object: Vajra & Bell Main Page.” Himalayan Art Resources, https://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=563. [An online archive of the different types of vajras and ghaṇṭās.]

Louise, Rita. “The Vajra – The Ancient Weapon Of The Gods” Youtube, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=10yLDbscgyA. [A video on the range of ancient weapons used by Gods across a number of civilisations and cultures, including India, Greece, Australia, Nordic countries and the Americas.]

Donyo, Thupten. “Hand Mudras: How to Use the Vajra and Bell.” YouTube, YouTube, 28 July 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vvNXC1Z2vY4. [In this video, Ven. Thupten Donyo teaches how to use the vajra and ghaṇṭā in traditional Buddhist ceremonies, introducing both the mudras used and chants recited.]

Robyn, let me just say that this entry was very impressive. Having little knowledge as to what a Vajra was prior to reading this, I can say that I learned a lot. You were extremely detailed in your descriptions, as well as super organized in your presentation. Your use of external links by incorporating them into the main paragraphs of your entry really made it flow, and showed where exactly they would fit into your topic. Additionally, I really enjoyed the wide variety of art you used. Great job!

I had barely any idea of what a Vajra was until I read this entry. It was very educational and explained the Vajra so clearly. You hit the physical aspect and the symbolic aspect of the tool. It was nice how you included little site references throughout the encyclopedia so I could figure out specifically where I could further read about a specific topic on the Vajra. I’m curious to know if there’s any debate over the fact that it’s considered a weapon in association with compassion and Upaya. Nice job.