Dharma is a Sanskrit term that derives from the root Dhr, meaning to uphold and maintain. The term originates from ancient Indian religions and is a crucial concept in religions such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and others. Dharma originally denotes natural law or “that which is established” (Willemen 2003, 217). When understood in the context of the root Dhr, dharma thus means upholding the natural law of the universe (Creel 1972, 156). Dharma has several different definitions across various religions. In the Buddhist tradition, however, dharma mainly refers to the teachings of the Buddha–although it can also mean things or phenomena.

Dharma is one of the Three Jewels, known as Triratna in Sanskrit. The Three Jewels (also sometimes called Three Treasures) are comprised of the buddha (teacher), the dharma (teaching), and the sangha (community of monks, nuns, and novices), all of which are fundamental aspects of the Buddhist path (Gethin 1998, 34). Buddhists vow to take refuge in the Three Jewels. The vow for refuge reads:

To the Buddha I go for refuge; to the Dharma I go for refuge; to the Sangha I go for refuge.”

The Foundations of Buddhism, (Gethin 1998, 34)

By taking this vow, Buddhists vow to make the Three Jewels the main principles in their lives in order to awaken from uncertainty. On the Buddhist vow of refuge, Tibetan meditation master Chögyam Trungpa writes:

Taking refuge is a matter of commitment and acceptance and, at the same time, of openness and freedom. By taking the refuge vow we commit ourselves to freedom.”

The Heart of the Buddha: Entering the Tibetan Buddhist Path, (Trungpa 2010, 375)

This vow to take refugee in the buddha, the dharma, and the sangha commits one to the Buddhist path, giving up all security and acknowledging that one is groundless–”the only thing to do is to relate with the teachings and with ourselves” (Trungpa 2010, 377). Some Buddhist scholars consider the dharma to be the most significant of the Three Jewels since, unlike the Buddha, the dharma still remains and thus serves as the closest connection to the Buddha.

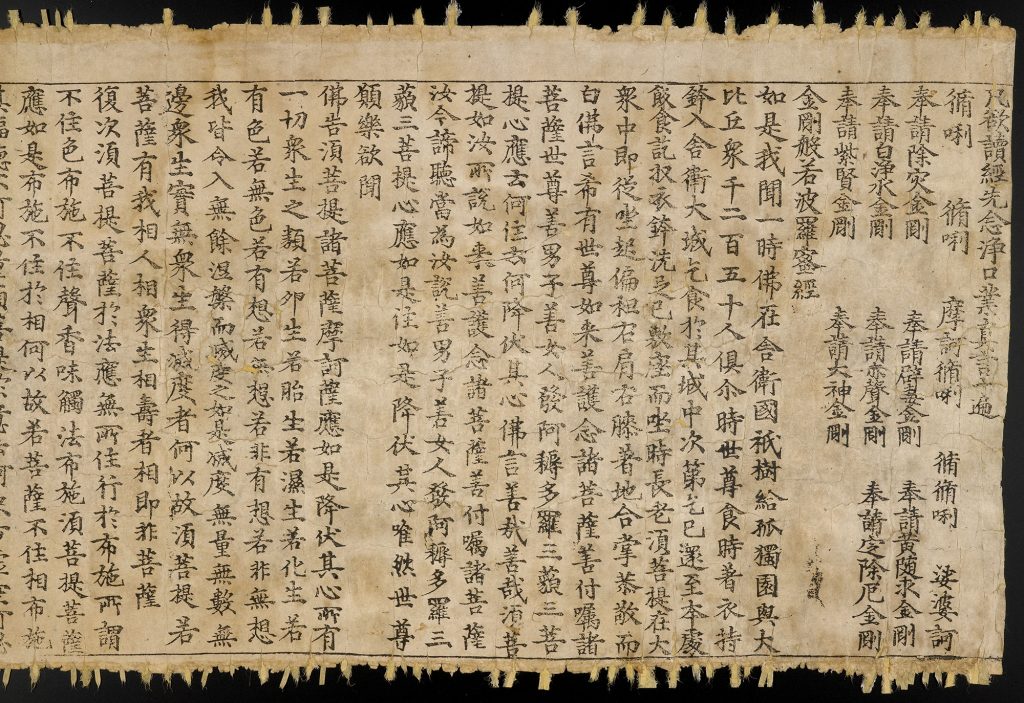

When referring to Buddhist teaching, the term dharma encompasses Buddhist texts. The Pali Canon of Buddhist scriptures is called the Tipitaka (Pali) or Tripitaka (Sanskrit) and is comprised of three collections. Indeed, the term Tripitaka consists of “tri”, meaning three, and “pitaka”, meaning basket. Tripitaka thus translates to “Three Baskets” (Hinuber 2003, 626). The first basket of the Tripitaka is the Vinaya Pitaka, which delineates monastic rules and procedures for the Buddhist community. The second basket is the Sutra (Sanskrit) Pitaka and consists of the Buddha’s discourses and sermons which are said to have been recorded by the Buddha’s disciples. Lastly, the Abhidharma (Sanskrit) Pitaka is the third basket. The Abhidharma (or “higher dharma”) Pitaka contains scholastic analysis of the material and psychological worlds and makes direct links between these outer and inner worlds. These three categories within the Tripitaka are considered dharma because they contain the teachings of the Buddha.

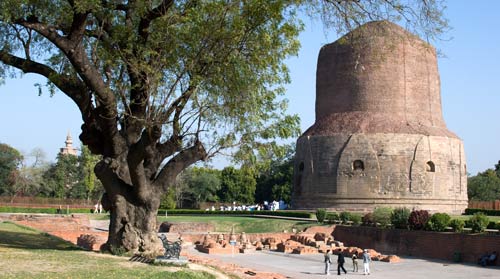

The first instance of the Buddha’s dharma is the “Dharmachakrapravartana Sutra” (sanskrit), or “Setting the Wheel of Dharma in Motion” (Miles 2015, 177–181). This Sutra is known to be the Buddha’s first sermon which he delivered after reaching enlightenment. Schaeffer’s translation of The Life of the Buddha describes how, prior to delivering this sermon, the Buddha “refreshed himself and wondered where he might begin to turn the wheel of dharma” (2015, 70), meaning this was the first instance of the Buddha turning the wheel of dharma by relaying his teaching. In this Sutra, the Buddha presents the Four Noble Truths, or the Truths of the Noble Ones. These truths are the truth of suffering (dukkha), the truth of the causes of suffering, the truth of cessation of suffering, and the truth of the path. The truth of suffering asserts that all existence is suffering (dukkha) and encompasses physical pain and illness as well as milder discomfort and mental tension. The second noble truth identifies the three poisons of desire, aversion, and ignorance as the root causes of all suffering. Alternatively, the third noble truth describes the possibility of freedom from suffering caused by desire, aversion, and ignorance by attaining Nirvana–reaching enlightenment. Lastly, the fourth noble truth contains the eightfold path, which is a description of eight divisions of following that lead to liberation. This eightfold path describes a middle way which avoids either extremes of pursuing sensual happiness or total asceticism (Miles 2015, 177). “Setting the Wheel of Dharma in Motion” is thus regarded as the Buddha’s first teaching, or first turning of the wheel of dharma, which asserts what followers of Buddhism should do and what the Buddha had already achieved.

The symbolic representation of dharma is a spoked wheel called the dharmachakra (Sanskrit), which is one of the oldest symbols of Buddhism. This symbol was once used to represent the Buddha before images of the Buddha were depicted, thus representing the Buddha through the symbol of his teachings. The word dharmachakra is translated as wheel (chakra) of the law (dharma) and signifies the Buddha’s Dharma (Simpson 1996, 27). The dharmachakra is often presented with 8 spokes, a representation of the eightfold path that the Buddha delineated in this first sermon which set the wheel of dharma in motion (Simpson 1996, 58). Other versions of the dharmachakra may depict a greater number of spokes, representing different parts of the Buddha’s Dharma. For instance, a dharmachakra with twelve spokes may symbolize the twelve links of dependent origination that the Buddha taught. Other aspects of the dharmachakra are symbolically significant as well, such as the circular shape of the wheel which symbolizes the perfection of the Buddha’s teachings (Issitt & Main 2014, 186). Additionally, the wheel’s rim is said to be significant by symbolically holding Buddhist practice together through meditation and concentration (Issitt & Main 2014, 186). Finally, the center hub of the wheel symbolizes moral discipline and often portrays three twisted marks which represent the Three Jewels (Issitt & Main 2014, 186). The dharmachakra remains one of the most significant, ancient symbols of Buddhism on a universal scale.

References

Chögyel Tenzin. The Life of the Buddha. Translated by Kurtis R. Schaeffer, Penguin Classics, 2015. [A biography on the Shakyamuni Buddha’s life that details the twelve acts of the Buddha.]

Creel, Austin B. “Dharma as an Ethical Category Relating to Freedom and Responsibility.” Philosophy East and West, vol. 22, no. 2, 1972, pp. 155–168. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1398122. [A scholarly exploration of the ethical implications of dharma and its ideological relation to other Buddhist terminology.]

Gethin, Rupert. The Foundations of Buddhism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. [A comprehensive introduction to Buddhist principles and practice. Describes the Three Jewels and the importance of taking refuge in them.]

Issitt, Micah L., and Carlyn Main. Hidden Religion: the Greatest Mysteries and Symbols of the Worlds Religious Beliefs. ABC-CLIO, 2014. [An encyclopedia of symbols across world religions that includes historical analysis of symbolic development and shared aspects of religious symbolism between various religions. This source was used to decode the symbolic meaning behind the various components of the dharmachakra.]

Miles, Jack, and Donald S Lopez, editors. “Setting the Wheel of Dharma in Motion.” The Norton Anthology of World Religions: Buddhism, Norton, W. W. & Company, Inc., pp. 177–181. [Text of the Buddha’s first sermon.]

Simpson, William. The Buddhist Praying-Wheel: the Symbolism of the Wheel and Circular Movements in Custom and Religious Ritual. Aryan International Books, 1996. [An educational examination of Buddhist praying wheels and the larger religious symbolism of wheels and circular representations in Tibetan Buddhism].

Trungpa Chögyam, and Judith L. Lief. The Heart of the Buddha: Entering the Tibetan Buddhist Path. Shambhala, 2010. [A presentation of Buddhist teachings written by master of Tibetan meditation Chögyam Trungpa. Trungpa relates Buddhist teachings–such as the Vow of Refuge–with contemporary life issues in order to teach Buddhist practice to a Western audience.]

von Hinuber, Oskar. “Buddhist Literature in Pali.” Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Macmillan Reference, 2003, pp. 217–224. [A detailed encyclopedia entry defining the Pali Canon included in the Encyclopedia on Buddhism, which contains almost 500 articles on Buddhist terminology.]

Willemen, Charles. “Dharma and Dharmas.” Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Macmillan Reference, 2003, pp. 217–224. [A detailed encyclopedia entry on dharma included in the Encyclopedia on Buddhism, which contains almost 500 articles on Buddhist terminology.]

External Links

A recorded lecture on the Buddhist vow of refuge given by Ogyen Trinley Dorje, the 17th Karmapa, can be found here. The Karmapa is the head of the Karma Kagyu school, one of the four main schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

To view objects and their descriptions from the exhibition “Dharma and Punya–Buddhist Ritual Art of Nepal” please click here. This exhibition features ritual art of Nepal centered around the Buddha’s Dharma and illustrates common practices in ancient Nepal intended to accrue good karma, which was a major principle of the Buddha’s Dharma. The exhibition symposium will be held on December 5th-7th at Harvard University and the exhibition itself will open from December 5th-14th at College of the Holy Cross. Attendance is free for both events.

For a comprehensive overview of each of the Four Noble Truths please visit this link.

For free access to full-text translations of any of Sutra click here. This website is intended to continue the spread of Buddha Dharma in the 21st Century.

Poet Anne Waldman speaks on the Buddha’s Dharma (including refuge and Bodhisattva vows) in connection with her book Vow of Poetry, and performs her own contemporary poetry at the Harvard Divinity School, available here.

Further Readings

McArthur, Meher. Reading Buddhist Art: an Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs and Symbols. Thames & Hudson, 2004. [A thorough examination of over 300 Buddhist symbols, objects, and figures throughout history. Includes photographs, diagrams, and maps for referencing location. Useful for further understanding the symbolic interpretations of the dharmachakra).

Batchelor, Stephen. After Buddhism: Rethinking the Dharma for a Secular Age. Yale University Press, 2017. [A critical interpretation of Buddha Dharma through a secularized lens. Includes earliest texts from Buddhist canon.]

Freiberger, Oliver. “The Buddhist Canon and the Canon of Buddhist Studies.” Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, vol. 2, no. 27, 2004, pp. 261–284. [A further examination of the Buddhist canon that disputes traditional criticisms of canons as sources for historical research. Argues the scholastic value of canons through the example of early Buddhist laity.]

Sangharakshita. The Essential Teachings of the Buddha. New Age Books, 2007. [An exploration of Buddha Dharma that presents core principles of Buddhism.]

Hello Lilly,

You wrote that some Buddhists believe that the dharma is the most important of the Three Jewels because, unlike the Buddha, the dharma still remains in the present day. In my encyclopedia entry for relics, I discussed how some Buddhists view relics as literal living remains of their associated figure—an object in which the figure can live on, even after cremation. There are a number of relics associated with the Buddha. I wonder how the Buddhists that you referenced (those who consider the dharma to be the most important of the Three Jewels, even more important than the Buddha) would interpret relics, and if they consider them to be living embodiments of their figures. The interpretation of relics differs from person to person, so this isn’t an inconsistency that I’m pointing out. I just wonder how those Buddhists would compare the ‘living’ relics to the ‘living’ dharma. I suspect that because the impact of the dharma is more widespread and persistent than the impact of relics, they would still consider the dharma to be the most important of the Three Jewels, even if they did hold the belief that relics are literal living embodiments of their associated figures.

Lily, I enjoyed reading your entry on Dharma— a topic I was interested in learning about. I was especially interested in learning about the historical evolution of the term and its relation to other terms in the Buddhist religion. On the whole, I think you brought the idea to life and made me learn the significance. Just a minor organizational suggestion is that would be easier to follow if you split your post into subsections. Other than that, good job!

This article is very useful for me and this is a quality article.

This article really helped me in understanding things that I didn’t know and this article is very high quality.