The most simple definition of a bodhisattva, and a good starting point, is “one on the path to Buddhahood” (Gethin 319). In order to understand the term in greater depth, it is necessary to gain a greater understanding of the concept of bodhicitta and the Mahayana Buddhist tradition as a whole.

Mahayana Buddhism and Bodhisattvas

The Mahayana Buddhist tradition developed following the emergence of “new” sutras around the first century BCE. Although they emerged long after the death of Siddhartha Gautama, these sutras were said to have been originally “delivered by the Buddha himself” but “not taught until the time was ripe” (Gethin 224-225). Mahayana Buddhism can be seen almost as a continuation of the Theravada school (Suzuki 573). The Mahayana sutras argued that the end of the path was not nirvana, as in the Theravada tradition. Instead, the end goal was buddhahood or complete enlightenment (Gethin 228).

With the development of Mahayana Buddhism came a new role model for its practitioners: the bodhisattva. This model is essential to the tradition, with Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki even going as far as to refer to Mahayana Buddhism as the “Buddhism of Bodhisattvas” (Suzuki 565). A bodhisattva is one who not only works to attain complete enlightenment, but also wishes to be reborn in order to help others achieve enlightenment as well. This contrasts with the Theravada role model of an arhat, since the Mahayana tradition focuses on the motivation behind the bodhisattva’s practice. However, the path of a bodhisattva is also understood as a continuation of the arhat’s path. It is argued that “these goals are… devices employed by the Buddha” in order to encourage people to start following the path, since the goal of an arhat seems more attainable than the goal of a bodhisattva and complete enlightenment (Gethin 228).

The responsibilities and practices of a bodhisattva are described in depth in Shantideva’s “The Way of the Bodhisattva.” Shantideva focuses on the role of a bodhisattva in the context of serving others for the majority of the poem. He speaks of this desire to improve the lives of others in the following lines:

“May I be a guard for those who are protectorless,

A guard for those who journey on the road.

For those who wish to cross the water,

May I be a boat, a raft, a bridge.”

Something to note in this quote is the presence of samsara. Figuratively, in order for one to be a guard for others, one must put themselves in harm’s way. Likewise, in order to be a boat “for those who wish to cross the water,” Shantideva has to expose himself to the danger of the water (Shantideva 49). Rupert Gethin references this concept in “The Foundations of Buddhism.” He writes that “the bodhisattva thus at once turns away from samsara as a place of suffering and at the same time turns back towards it out of compassion for the suffering of the world” (Gethin 229). In this way, a bodhisattva’s practice and rebirth are motivated by a wish to help other living beings. This focus on a practice motivated by compassion brings us to the concept of bodhicitta.

Bodhicitta

Bodhicitta can be translated as “awakening mind” (Gethin 230). Compassion is often seen as central to this awakened mind state. “Bodhicitta, as awakening mind, is the intention to awaken to life in order to help others awaken to life” (McLeod). Another quote from “The Way of the Bodhisattva” references this concept:

“Likewise, for the benefit of beings,

I will bring to birth the awakened mind,

And in those precepts, step-by-step,

I will abide and train myself.”

Shantideva’s commitment to “abide and train” himself for the benefit of others exemplifies the concept of bodhicitta. This reflects that his “awakened mind” is guided by a wish to benefit other beings (Shantideva 50). This concept is linked to compassion, but they are not the same. Bodhicitta “may grow out of the compassion that seeks to alleviate suffering, but it is qualitatively different” (McLeod). Instead, bodhicitta reflects a bodhisattva’s intentions behind their practice and a focus on liberation of others.

The Buddha as a Bodhisattva

The Buddha himself is often referred to as a bodhisattva. Although it is said that he was already enlightened before he took the form of Siddhartha Gautauma, the Buddha’s motivations are characteristic of a bodhisattva. Before he began his final life in the human realm, he expressed his desire to serve as a refuge for those living beings who experience suffering. Specifically, he vowed to “set free those who are not free” (Chogyel 10). This desire to be reborn in order to help others achieve liberation is a clear example of bodhicitta, and marks the historical Buddha as a bodhisattva.

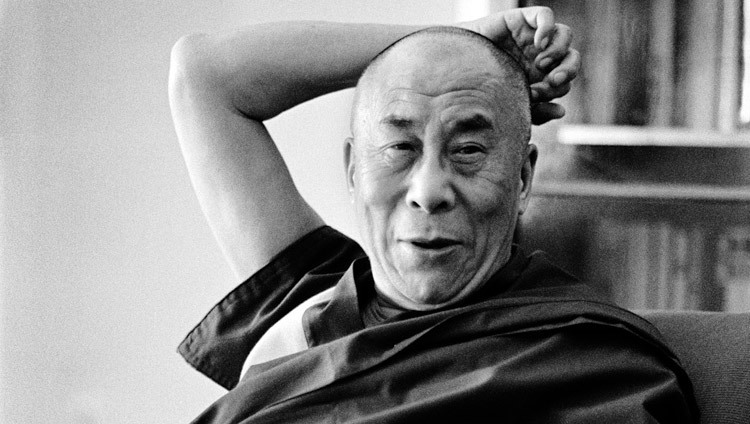

The Dalai Lama as a Bodhisattva

It is helpful to consider a modern example of a bodhisattva. The Dalai Lama is an extremely visible figure, due to his work around the world and advocacy for the Tibetan people. He is believed to be a reincarnation of the Bodhisattva of Compassion, Avalokiteshvara. On his website there is a clear focus on his role as a bodhisattva, especially in regards to bodhicitta. Bodhisattvas are described on his website as “realized beings, inspired by the wish to attain complete enlightenment, who have vowed to be reborn in the world to help all living beings” (“The Dalai Lama”). The Dalai Lama’s work reflects this, with his many teachings given around the world in order to help bring liberation to more living beings. His advocacy for peace also reflects a desire to alleviate suffering.

References

“Bodhisattva 11th–12th Century.” Metmuseum.org, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/36085. [Image of bodhisattva sculpture.]

“Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in Water Moon Form (Shuiyue Guanyin).” Metmuseum.org, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/42731. [Image of Avalokiteshvara sculpture.]

Chögyel Tenzin, and Kurtis R. Schaeffer. The Life of the Buddha. Penguin Classics, 2015. [A translation of Chögyel’s account of the historical Buddha’s life.]

Gethin, Rupert. Foundations of Buddhism. Oxford University Press, 2014. [Gethin explains many central topics and terms of Buddhism in his book.]

McLeod, Ken. “What Is Bodhicitta in Buddhism? Ken McLeod Explains.”

Tricycle, https://tricycle.org/magazine/what-is-bodhicitta/. [McLeod gives an explanation of the concept of Bodhicitta and its applications.]

Shantideva, and Padmakara Translation Group. Way of the Bodhisattva. Shambhala Publications Inc, 2006. [A translation of Shantideva’s poem detailing the path and motivations of a bodhisattva.]

Silk, Jonathan A. “Bodhisattva.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 26 Apr. 2016, https://www.britannica.com/topic/bodhisattva. [A general overview of the Buddhist ideal of a bodhisattva.]

Suzuki, Daisetz Teitaro. “The Development of Mahayana Buddhism.” The Monist, vol. 24, no. 4, 1914, pp. 565–581. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27900506. [A short overview of the development of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition.]

“The Dalai Lama.” The 14th Dalai Lama, 26 Nov. 2019, https://www.dalailama.com/the-dalai-lama. [Official description of the Dalai Lama’s position and duties.]

External Links

To watch the Dalai Lama give a talk on the importance and benefits of bodhicitta follow this link.

For a video discussing more differences between the Mahayana and Theravada traditions follow this link.

To listen to a podcast on cultivating bodhicitta follow this link.

Further Readings

Larson, Kay. “Avalokiteshvara: The Changing Face of Compassion.” Lion’s Roar, 3 Dec. 2018, https://www.lionsroar.com/who-is-avalokiteshvara/. [A discussion of the image of Avalokiteshvara over time and in a variety of cultures.]

Silk, Jonathan A. “Mahayana.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1 Aug. 2017, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mahayana. [A broad overview of the Mahayana tradition as a whole with references to bodhisattvas.]

Weininger, Radhule. “The Bodhicitta Effect.” Shambhala, 13 July 2018, https://www.shambhala.com/the-bodhicitta-effect/. [An article on the “bodhicitta effect,” or the real world effects of cultivating bodhicitta.]

One of the strongest parts of the entry is when you use a combination of primary sources and secondary scholarship to produce a really original passage that teases out the role of the Bodhisattva. In fact, the way that you’ve chosen to include short quotes throughout your entry provides us with helpful context without leaning too much on others’ writing. It’s not an easy task to explain the relationship of the Theravada and Mahayana traditions, but you transition gracefully through the history, the similarities and differences remain clear and relevant to the purpose of your entry. I thought the choice to conclude your entry with a look at the Dalai Lama was a clever way relate the traditional concepts of Bodhisattva and bodhicitta to contemporary Buddhism. However, I think that your entry would be slightly easier to read if you had put the section titled “The Buddha as a Bodhisattva” earlier in the piece, or even incorporated the content into one of the other sections. Obviously, the Buddha is central to Buddhism and Bodhisattva and it comes off as an afterthought when you position it towards the end of the piece.

This entry effectively described the roles of Bodhisattvas and the concept of Bodhicitta in Buddhism. One reason why it was easy to follow was because it was so thoughtfully organized: you first gave a brief, and broad definition of a bodhisattva and then you narrowed down your focus, ending with a description of the Dalai Lama, a modern example of a bodhisattva.

I loved the three images of bodhisattvas. It is super interesting to be able to see a picture of Dali Lama, the modern-day bodhisattva, contrasted with historic sculptures of bodhisattvas from the 11th century. I also liked how you included an external link on how to cultivate the bodhicitta, allowing the reader to apply the concept to his/her own life.

One thing that I am left a little confused about is the differentiation between an “awakened mind” and compassion. You write that they are linked concepts but they are not the same. Then, you go on to say that bodhicitta focuses on librations of others but isn’t that the same as being compassionate?

Despite that minor point of confusion, your entry was both compelling and straightforward.