Cosmology refers to the origin, process, and structure of the universe. In traditional Buddhist philosophy, the cosmology of the universe is marked by infinite vastness in both space and time. Spatial cosmology describes the arrangement of the infinite number of worlds in the universe while temporal cosmology describes how those worlds come into existence and the cyclic nature of the creation and destruction of them (Gethin 1998, p.131). While Buddhists believe there to be no true beginning of the universe as it is forever existing in one form or another, each world system comes into existence in a specific nature.

In the Aggañña sutta, the Buddha describes the origin of life. According to the Buddha, between the presence of world systems, all beings exist as self-luminous beams of light in the “realm of the Radiant.” In this state, beings have no form and move through the air as energy. After an unspecified period of time, a world begins to evolve beneath the beings in the realm of the Radiant. This world starts as a surface of water surrounded by darkness. As the beings come down closer to the world, a milky substance referred to as the “Essence of Earth” spreads out over the water. The beings become hungry and feed off of this substance resulting in a loss of their self-luminosity due to this act of greed. In turn, the sun and moon are created at this moment. The beings become coarser and coarser as a soil forms over the Earth. In these very early moments, the form and evolution of the world are influenced by the positive and negative acts of the beings. This sets the foundation for the importance placed on all acts of body, speech, and mind in determining one’s fate in the cosmos. Society slowly evolves to form a social hierarchy including the traditional classes of the ruler class, the brahmin class, the trader class, and the servant class. The Buddha explains that although society can be divided into these distinct classes, ultimately what matters in one’s life is not the class to which one is born, but rather the actions and intentions throughout one’s lifetime. In the Buddhist origin of life story, there is no creator being. Instead, new worlds are set forth using the power of accrued karma of all beings in their previous lifetimes. These beings simply come into existence over time, exist, and then eventually will cease to exist in that form. Beings are born and reborn into various different realms in the world system based on the karma of all of their past lives (Aggañña sutta, 80AD).

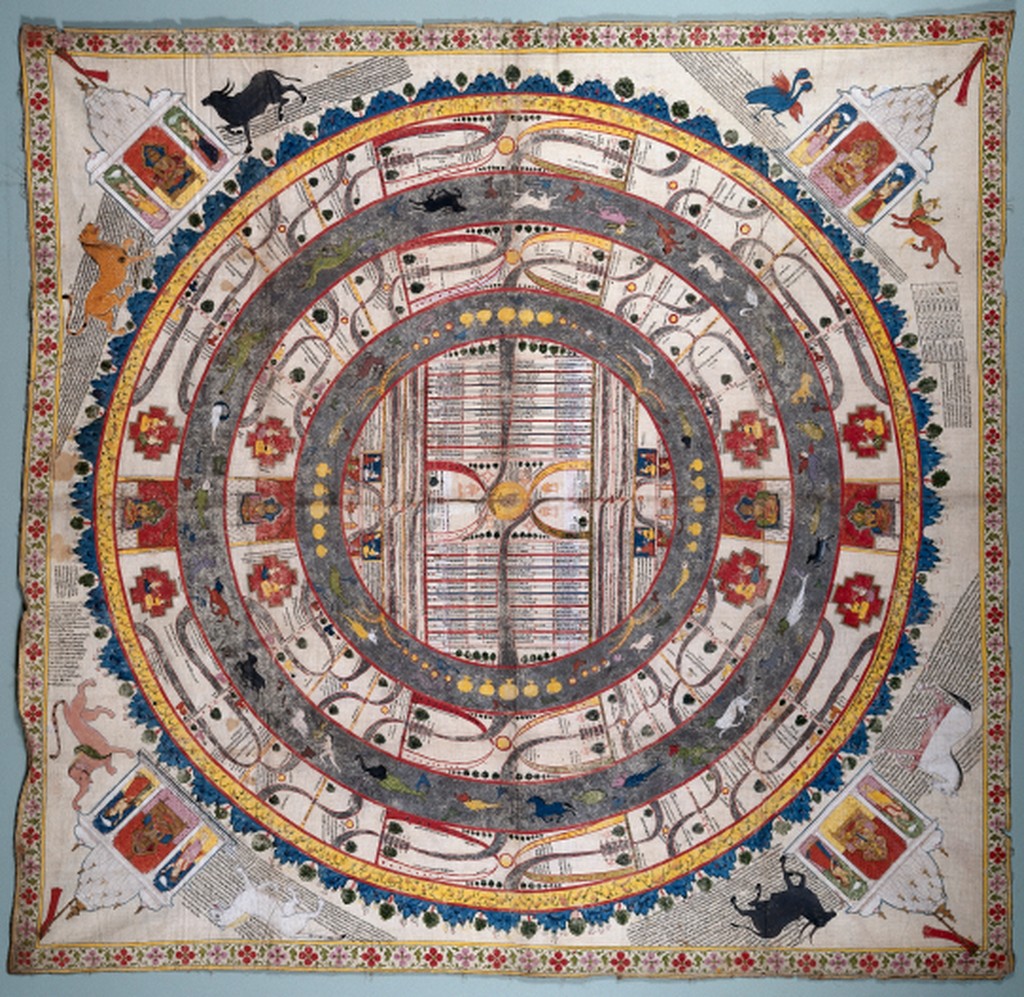

The oldest Buddhist philosophy, the Hīnayāna tradition, outlines a single world system in which the universe consists of a flat, golden disk with a large mountain, Mount Meru, at the center. There are seven circular mountain ranges arranged concentrically around Mount Meru. Surrounding these mountains are great seas of infinite size. Four distinct land masses are situated in this great ocean, one at each direction of a compass. Pūrvavideha exists to the east, Jambudvīpa to the south, Aparagodānīya to the west, and Uttarakuru to the north. There are eight subcontinents also in the great sea located to each side of the four main continents. It is said that human life exists solely on the southern continent, Jambudvīpa, and that this is also the only continent in which a Buddha will appear. On the continent of Jambudvīpa, the lifespan of a human is incalculable in the early stages of the world system, but slowly diminishes as time goes on, until it reaches just one year (Kloetzli 2005, p. 2026-2027).

Beneath Jambudvīpa are the eight hot hells and the eight cold hells descending from the bottom surface of the disk. Above Mount Meru exist a series of heavens arranged into three divisions: (1) the six heavens in the “realm of desire”; (2) the seventeen heavens in the “realm of form”; and (3) the four heavens in the “realm of non form.” In this single-world system, a monk will travel all the realms of the universe and eventually go beyond them to achieve individual Nirvana and the state of arhat. From this original concept of a single universe evolved the idea of a ten-thousand-world system, and then eventually the cosmology of the Mahāyāna tradition characterized by innumerable world systems (Kloetzli 2005, p. 2027). These two beliefs are characterized by the same spatial organization described above, just a vast number of these world systems dispersed throughout the multiverse. With these two concepts of cosmology emerges the importance of temporal cosmology in addition to spatial cosmology.

The Buddhist multiverse, while infinite in its temporal cosmology, can be broken into several divisions of time periods. The largest measured division of time, which corresponds to the duration of the universe, is referred to as a mahākalpa which consists of four “moments” called kalpas. The mahākalpa consists of: (1) a kalpa of creation in which the world system is created; (2) a kalpa of duration in which the world system and all beings exist; (3) a kalpa of dissolution in which the world declines and is eventually completely destroyed; and (4) a kalpa of vacuity in which the world remains dissolved and nothing exists but empty space (Karuna 2006). Each of these four kalpas are incomprehensibly vast in length. The events of a kalpa of creation are detailed above in which beings of light descend to a slowly evolving world. In a kalpa of duration, each being exists in one of the thirty-one realms of rebirth. The realm in which a being exists is determined by their accrued karma from all previous lives. In a kalpa of dissolution, the entire world system is destroyed by either fire, water, or wind over a period of time (Gethin 1998, p. 124). All beings are destroyed but will soon be reborn into another realm or a different world system altogether. During a kalpa of vacuity, the specific world system in the cycle no longer exists, but due to the vastness of the cosmos, there are always an infinite amount of other world systems in existence at any given moment.

The organization of the Buddhist cosmos remain important to everyday life as knowledge of these realms of existence and cycles of world systems provide guidance for humans. An awareness of the conservation of karma from one lifetime to another can influence how followers of the Buddha choose to live their lives, attempting to make good decisions and avoid poor ones in hopes of rebirth in a favorable realm of the universe.

References

Aggañña Sutta. “The Origin of Things.” The Collection of Long Sayings, 80AD.

Gethin, Rupert. The Foundations of Buddhism, Oxford University Press USA – OSO, 1998. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/wesleyan/detail.action?docID=684592.

Ikeda, Daisaku, et al. Buddhism and the Cosmos. Macdonald, 1986.

Karuna, Tri Ratna Priya. “Buddhist Cosmology.” Buddhist Cosmology, 2006, www.urbandharma.org/udharma2/budcosmo.html.

Kloetzli, W. Randolph. “Cosmology: Buddhist Cosmology.” Encyclopedia of Religion, edited by Lindsay Jones, 2nd ed., vol. 3, Macmillan Reference USA, 2005, pp. 2026-2031. Gale eBooks, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.wesleyan.edu/apps/doc/CX3424500664/GVRL?u=31841&sid=GVRL&xid=2d6810b5. Accessed 26 Nov. 2019.

External Links

For an extensive overview of time, space, and being through a conversation between Ajahn Sona and Ajahn Punnadhammo, two monks from a monastery in Canada, click this link. This video is the first of a ten-part video series that explains Buddhist cosmology in great detail through conversation.

For more information about realms of rebirth, samsara, and dependent origination, click this link. This blog post written by a Buddhist nun belongs to a larger collection of posts and other helpful links for both scholars and followers of the religion.

The structure of the Buddhist cosmos can be difficult to grasp in two dimensional images. Click here for several three dimensional models of the Mount Meru world system.

Further Readings

Lopez, Donald S. “First There Is a Mountain (Then There Is No Mountain).” Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, 2008, tricycle.org/magazine/first-there-mountain-then-there-no-mountain/. [A magazine article that analyzes the potential legitimacy of Buddhist cosmology by exploring it from a scientific perspective. Sheds light on whether the Buddhist world system is a real possibility based on scientific knowledge.]

Mitchell, Donald W. “The Trinity and Buddhist Cosmology.” Buddhist-Christian Studies, vol. 18, 1998, pp. 169–180., doi:10.2307/1390452. [An interesting look at the Buddhist Cosmos through comparisons with traditional Christian philosophies.]

Yamamoto, Shuichi, and Victor S. Kuwahara. “Modern Cosmology and Buddhism.” Journal of Oriental Studies 18 (2008): 124-131. [An essay that compares the Buddhist origin story with other widely accepted origin stories including the Big Bang Theory and the Steady-State Cosmology Theory.]

This post demonstrates a clear understanding of Buddhist cosmology and it was very easy to follow. I found your second paragraph outlining the origins of life from the Buddha’s perspective, particularly valuable in providing a holistic perspective on Buddhist cosmology. Consequently, I found that the images you chose complemented the main themes in your entry. One suggestion I would have for this entry is mentioning how some Buddhist’s view the different realms as different psychological states.

Hi Alex!

Thank you for your work on the Buddhist Cosmology, I really liked how you emphasised both the spatial and temporal cosmologies and tracked the development of these ideas over the Hinayana and Mahayana traditions.

I have a few suggestions that you may want to take into consideration:

Firstly, I believe many encyclopaedia articles have sub-headings or sub-categories. It would be helpful if you added some. (e.g. origin of the universe, spatial cosmology, temporal cosmology, end of the world, etc). Generally this helps highlight what topic the reader should be focussing on and shapes the narrative of the article itself.

Secondly, with regards to your paragraph on the Aggañña sutta, I understand that you’re trying to explain the origin of the world through the sutta but it feels like you’re just summarising the sutta. Moreover the summary of the sutta seems to be inconsistent – you start off more narrative and then move to being more analytical. If I were you (and knowing how repetitive the narrative of the sutta is) I would just jump straight to the main analytical points of the sutta. For example, that our world began perfect and became imperfect because of vice, creating societal concepts like gender, class, etc. and then introduce the concept of karma. I did, however, like how you segued from a lack of a creator being to introducing the concept of rebirth. That was really nice!

Great post! I learned something new and interesting, which I also happen to cover on my blog. It would be great to get some feedback from those who share the same interest about Cosmetics, here is my website FQ4 Thank you!