Overview

Dependent origination is a central etiological principle of Buddhist philosophy that describes the emergence of suffering (dukkha) from its roots in the ignorance of the Four Noble Truths. It is often presented in systematized form as the Twelve Links of Dependent Arising. The doctrine of dependent origination, and the “standard” twelvefold causal chain accompanying it [1], are codified in the Mahanidana Sutta in the Pali canon [2]. The principle of dependent origination interfaces with a number of other key concepts in Buddhist philosophy, such as karma, emptiness (śūnyatā), and no-self (anattā); differences in interpretation of dependent origination across different schools of Buddhism can sometimes be approached by analyzing the emphases given to particular related principles.

According to Rupert Gethin, dependent origination at the most basic level rejects random causality and asserts the existence of a deeper, fundamental structure governing temporal sequences of events [3]. Importantly, early texts on the topic contend that the isolation of single causes and single effects is erroneous; instead, the convergence of multiple causes produces a multiplicity of effects [4]. This rich, complex view of causality, in which vast networks of causes are indexed to equally vast networks of effects, informs a skeptical position regarding human behaviors of identifying and individualizing causes and subsequent effects. As Jay Garfield writes, “carving out particular phenomena for explanation or for use in explanations depends more on our explanatory interests and language than on joints nature presents to us” [5] [A].

The Twelvefold Chain

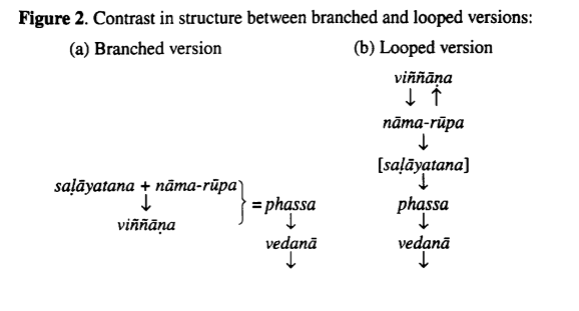

Dependent origination is commonly conceptualized through the lens of the Twelve Links of Dependent Arising; this heuristic device is often presented diagrammatically, either as a linear causal chain or sometimes in a looped form [6]. According to Bucknell, the twelvefold chain is best known as follows [7]:

| Link (English) | Nidana (Sanskrit) | Notes |

| Ignorance | Avijjā | Ignorance, particularly concerning the Four Noble Truths |

| Activities | Saṅkhāra | Volitional forces of body, speech, mind |

| Consciousness | Vijñāṇa | Eye-consciousness, ear-consciousness, nose-consciousness, etc. |

| Name-and-form | Nāma-rūpa | The mental faculties (nāma) and physical components (rūpa) of a living being |

| Sixfold sense-base | Salāyatana | Sense-organs (eye, ear, nose, tongue, body) as well as mind, considered to be a sort of internal sense-organ that mediates mental objects |

| Contact | Phassa | Contact between the sense-organs and the external world |

| Feeling | Vedanā | Pleasant, unpleasant, or indifferent feelings as a result of contact between the sense organs and the external world |

| Craving | Taṇhā | Craving for sensual experiences, including experiences of the mind with mental objects |

| Clinging | Upādāna | Attachment to “various courses of action as the means” [8] of satisfying cravings for pleasant sensual experiences |

| Becoming | Bhava | The repeated performances of courses of action directed at satisfying craving/clinging, which “become our particular ways of being” [9] |

| Birth | Jāti | Rebirth, as “conditioned by these very courses of action” [10] |

| Aging-and-death | Jarā-maraṇa | “Aging, decrepitude… death, disease” [11] |

The significance of the ordering of the twelve links as presented above is a major area of study for scholars of Buddhist thought. Gethin considers the standard construction of the chain with ignorance (avijjā) as the first link reinforces an understanding of ignorance as an active or positive state of being. Ignorance, on this view, is not so much a failure to obtain knowledge as it is a willful refusal to see things as they are [12] [B]. Other scholars have discussed internal inconsistencies in the linear organization of the twelvefold chain, and have raised the question of whether the twelve links are to be understood in a strictly synchronic, ordered fashion at all. For example, Bucknell, noting the reappearance of definitional features of nāma-rūpa in other nidanas further down the causal series, reflects: “these discrepancies could be explained away by suggesting that the causal links are not to be understood as strictly ordered, but that would amount to a serious weakening of the notion of causal dependence” [13].

Historical Context

It has been widely established by Buddhist scholars that the early records of the Twelvefold Chain as it was presented in the Mahanidana Sutta of the Pali canon was not a purely original formulation, but rather a synthesis of several older formulations from Vedic cosmogony. Joanna Jurewicz argues that “the Vedic cosmogony and the pratītyasamutpāda describe the creation of the conditions for subject-object cognition, the process of this cognition, and its nature” [14] [C].

Jurewicz notes the striking similarity between the Vedic notion that the Creator – while still in his ‘pre-creative state’ – was unable to cognize anything other than himself due to his total singularity, and the formulation of avijjā as it appears in the Buddhist formulation of dependent origination in the Pali sutta. While Buddhist dependent origination certainly does not hold that the individual constitutes a singularity that makes subject-object cognition impossible, the “darkness” of the Creator’s pre-creative state resonates with the failure to cognize the Four Noble Truths that characterizes avijjā [14].

External Links

Notes for Further Reading

[A] This quote is taken from Garfield’s interpretation of Nagarjuna, which puts forward a more austere reading of dependent origination, namely, that causes – construed to be events that contain or necessitate the consequences they are indexed to – do not exist, and that all that exist are myriad conditions, which can be paired with subsequent ‘effects’ as explanatory devices but do not exert some compulsory force on the conditioned phenomena. However, Garfield captures the spirit of the less severe position on causality, which is that in any case, human discernment of individual causes and effects is arbitrary and reflects most clearly our interest in their utility as explanatory devices.

[B] In a Dharma talk, Gethin remarks: “I suppose putting it [ignorance] first is making the point that that kind of refusal or reluctance to the world as it is… is quite deep, and colors a lot of the things we do.” Gethin does not argue this point explicitly, but he seems to suggest that by ascribing primacy to ignorance, early Buddhists sought to emphasize ignorance, the product of one’s own volition, as the ‘root’ of suffering. Ignorance was thus an affliction that the practitioner could target directly through using the force of their willpower to undermine the subsequent interdependent links in the causal chain of suffering.

[C] While Jurewicz’s article is largely concerned with identifying parallels between Vedic cosmonogy and the Buddhist pratītyasamutpāda, Jurewicz does take care to note the divergence over the existence of the ātman between the two traditions.

References

- Bucknell, Roderick S. (1999), “Conditioned Arising Evolves: Variation and Change in Textual Accounts of the Paticca-samupadda Doctrine”, Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 22 (2)

- “Maha-nidana Sutta: The Great Causes Discourse” (DN 15), translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu. Access to Insight (BCBS Edition), 30 November 2013, http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/dn/dn.15.0.than.html .

- Rupert Gethin – A Dharma Talk On Dependent Origination, Alternativot Publishing, 9 Feb. 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kUjG7DfCMPY.

- Ibid.

- Garfield, Jay L. “Dependent Arising and the Emptiness of Emptiness: Why Did Nāgārjuna Start with Causation?” Philosophy East and West, vol. 44, no. 2, Apr. 1994, https://scholarworks.smith.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1023&context=phi_facpubs.

- Bucknell, Roderick S. (1999), “Conditioned Arising Evolves: Variation and Change in Textual Accounts of the Paticca-samupadda Doctrine”, Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 22 (2)

- Bucknell, Roderick S. (1999), “Conditioned Arising Evolves: Variation and Change in Textual Accounts of the Paticca-samupadda Doctrine”, Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 22 (2)

- Gethin, Rupert. The Foundations of Buddhism. Oxford University Press, 1998. 151.

- Gethin, The Foundations of Buddhism, 151.

- Ibid.

- Bucknell, Roderick S. (1999), “Conditioned Arising Evolves: Variation and Change in Textual Accounts of the Paticca-samupadda Doctrine”, Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 22 (2)

- Rupert Gethin – A Dharma Talk On Dependent Origination, Alternativot Publishing, 9 Feb. 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kUjG7DfCMPY.

- Bucknell, Roderick S. (1999), “Conditioned Arising Evolves: Variation and Change in Textual Accounts of the Paticca-samupadda Doctrine”, Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 22 (2)

- Jurewicz, Joanna. “Playing with Fire: the Pratityasamutpada from the Perspective of Vedic Thought.” Journal of the Pali Text Society, 2000. 77.

Buy Gw2 Legendary Envoy Armor boosting to quickly unlock one of the most prestigious armor sets in the game. Let experts handle the grind, so you can wear the Legendary Envoy Armor with pride without spending countless hours.