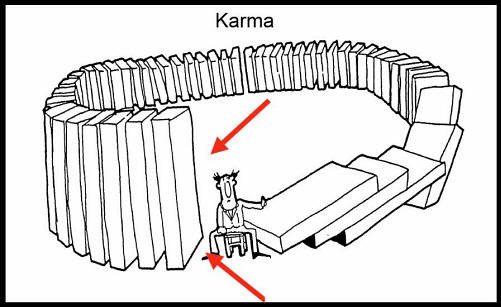

Karma is derived from the Sanskrit word “Karman,” which translates to action or deed. The doctrine of karma implies that the actions of an individual leave a karmic residue, where events in the past, as well as events in the present determine future contingencies. Therefore, “sow a thought to reap an act. Sow an act and reap a habit, sow a habit and reap a character, sow a character and reap a destiny. Or simply, what goes around comes around” (Dhiman, 37).

On synthesizing this quotation, a formula can be derived: cause = effect. According to this karmic universe, every premeditated action has a direct outcome on the individual, while it may also have an outcome on a third-party individual in the transfer of merit. Merit-making occupies a central role in the karmic theory of action, as it is equated with religious action in South and Southeast Asia. The fulfillment of the other modes of the Path of the Buddha: panna, samadhi and sila (wisdom, mental discipline and morality) is often deemed challenging to pursue to any considerable degree. Therefore, Buddhists and Buddhist monks alike place merit-making at the center of the practice of Theravada Buddhism. “Merit is seen as a form of spiritual insurance, an investment made with the expectation that in the future – and probably in a future existence – one will enjoy a relatively prolonged state without suffering” (Keyes, 267). The accumulation of merit/demerit in past lives as well as in one’s present life contributes to a karmic legacy, which could either relieve, prolong or eliminate states of suffering. This may also be true in in the case of easing another individual’s state of suffering through the transfer of merit.

The notion of transferring merit to ancestors originated in Vedic customs, but eventually became commonplace in many denominations: including Buddhism and Jainism. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad from the Brahmanical tradition describes a man appropriating to himself the good deeds of a woman with whom he engages with physically, as her “vulva is the sacrificial ground; her pubic hair is the sacred grass; her labia majora are the Soma-press; and her labia minora are the fire blazing at the center” (Bronkhorst, 92). In this particular instance, the man receives the goods deeds of the women and an unparalleled quantity of knowledge, while the woman appropriates to herself the good deeds of the man, without the exorbitant knowledge. This is demonstrative of how karma and merit go hand in hand.

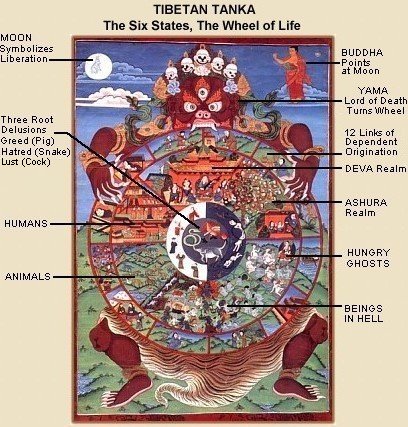

The same theory that is believed in the Brahmanical tradition can also be applied to Mahayana Buddhism. Numerous Buddhists not only devote themselves to the practice of Buddhism, but also to attaining a state of Buddhahood. These bodhisattvas undertake strict vows in order to accomplish the sacrificial journey to complete enlightenment. The path to enlightenment involves “taking on the suffering of others and transferring their own merits to them” (Bronkhorst, 95). Demerits function likewise. For example, in the Naraka (hell) section of the Realms of Rebirth, each hell hosts a particular type of individual for committing a sin. “A nihilist who claims that the truth is untruth is consumed by fire in Patapana hell” (The Realms of Rebirth, 7). This is representative of an individual’s actions affecting the domain in which they dwell. The fact that someone is consumed by fire implies that everyone within that hell would get consumed by the exact same fire, as punishment in this realm of existence spares nobody. Once consumed by the fire, they submit themselves to the bonds of karma setting samsara (cyclic existence) in motion. The performance of bad deeds transfers demerits across that particular realm of rebirth.

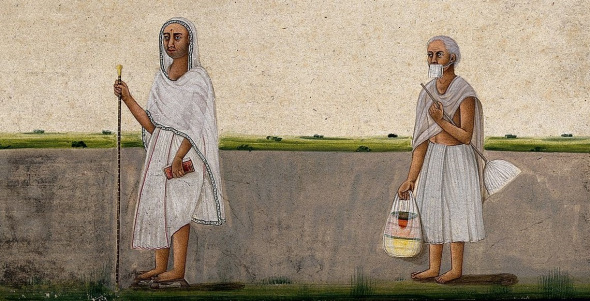

Karma, merit and ascetics also come to the fore in Jainism, although with varying mobility. There is a story where a young woman from Bombay travels to a shrine in Śańkheśvar Pārśvanāth to perform a three day fast hoping to improve her father’s health. Her fast (aththam) consisted of only minimal water on the second and third day. Devotional practices and ascetic rituals characterized the three days, as she hoped her father’s condition would ameliorate.

These ascetic undertakings involved mental and physical constraints to curb the cultivation of new karma, and eliminate the existing karma clinging onto her father’s soul. “Asceticism in the Jain tradition has a twofold goal: the prevention of new karma coming into contact with and thereby binding the soul, a process known in karma theory by the technical term of samvara; and the elimination of karma already in binding contact with the soul, a process known as nirjarā”(Qvarnström, 130). This is an example of how one can alter their karmic status to eliminate karma clinging onto the soul by transferring merit through sacrifice.

Karma and merit essentially boil down to the rational thought that allows us to remove ourselves from our conditioning, or that like the rest of the material universe, our actions are predetermined by past events. However, the Buddha argued that our capacity to acknowledge this rational dichotomy and to choose between one of two logically equal views is evidence of a will that can be freed from the subjective reasoning we acquire through individual experience. To assume a purely fatalistic perspective on our karmic destiny would imply the constant performance of good deeds in order to acquire merit to either transfer it onto another individual or to ensure rebirth into an ideal realm of existence.

References

Dhiman, Satinder, Gary E. Roberts, and Joanna E. Crossman. The Palgrave Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Fulfillment. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. [ The book establishes the doctrine of Karma and its place in Indian philosophy, while it also attempts to provide answers to how karma would play out on different personalities. The fatalistic aspect of this encyclopedia entry draws inspiration from the section “Does Karma imply fatalism?”, pages 37-41.]

Keyes, Charles F., and E. V. Daniel. Karma: An Anthropological Inquiry. Oakland: University of California Press, 1983.[The book discusses how karmic ethos finds expression in the discourse of Buddhists of the Theravadin tradition and the centrality of merit-making, pages 261-271.]

Bronkhorst, Johannes. Karma. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2011. [An account of the various texts giving expression to the fundamentally individual nature of karmic retribution and the transfer of merit, pages 91-96.]

Lopez, Donald. Buddhist Scriptures. London: Penguin UK, 2004. [A detailed cause-effect summary of the performance of good and bad deeds in the six realms of rebirth, pages 3-18.]

Qvarnström, Olle. Jainism and Early Buddhism: Essays in Honor of Padmanabh S. Jaini. Jain Publishing Company, 2003. [An alternative approach to karma and merit transfer, as seen by Jains. Commonalities and differences with Buddhism demonstrated, pages 129-133.]

External Links

For an insight on how karma is engrained in memory, click here to hear Sadhguru’s solution to letting go of our memory, in turn “breaking the karmic trap.”

A collection of abstract karmic art, alongside various depictions of Avalokiteshvara can be found here.

AJR, an American pop band produced the song karma. The song revolves around the band appealing to their doctor for not having already reaped the benefits of performing good deeds.

Further Readings

Holt, John C. Assisting the Dead by Venerating the Living: Merit Transfer in the Early Buddhist Tradition. Numen, 1981. [Determines how religious interpretations of death valorize the human meaning of life. Discusses the early intent of Buddhist monks to perform meritorious actions in order to release the cycle of samsāra.]

Bronkhorst, Johannes. Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism. Leiden: BRILL, 2011. [Provides parallels to the book cited above, Jainism and early Buddhsim. Contains arguments against Buddhism finding its roots in Vedic Brahmanism.

MacFarquhar, Larissa. How To Be Good. The New Yorker, The New Yorker, 2011. [Questions whether or not there is a connection between the positive karma we generate in one life and the quality of our life by providing scientific scenarios.]

Gethin, Rupert. Sayings of the Buddha: New Translations from the Pali Nikayas. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. [Expands on the Buddhist understanding that only intentional actions contribute to karmic residue.]

Hello Siddhant,

I find the concept of transferring or destroying karma to be very interesting, and I would like to know more about it. My understanding based on your writing is that one person’s actions, when carried out with great intention (i.e. the intention to transfer or destroy karma), can supersede the actions that another person has already carried out. This is especially the case in Jainism, where karma is destroyed through good acts and a devoted lifestyle. I wonder if this ‘breaks’ the idea of cause and effect. For example, if someone does something bad, but then that bad karma is ‘erased’ by someone else before the impacts of that bad action come back around, then is there a cause (the original bad action) without an effect (the bad thing coming back around)? Or could it be said that the original bad action somehow caused the karma-erasing action of another person? I am a bit confused on this topic and wonder how generally accepted into the Buddhist tradition(s) this is, or if it applies more to Jainism. I know you discussed the idea of karma transferring in the context of Buddhism, but this is slightly different than destroying karma.

Perhaps we can discuss over a cup of tea sometime.

I really enjoyed how you began with the etymology of karma and progressed into a deeper definition including how karma is seen by different groups of Buddhists. I also really liked your first image. It was a very simplistic but accurate representation of how karma functions. Perhaps my favorite part of your post is how you included a modern example of karma in your external sources so that a reader could see how it is applicable in ancient Buddhism, and also in the 21st century.

I really appreciate this post, I intend to teach my friend to make a blog. What do you recommend as a starting point?