The concept of samsara refers to the state of reincarnation through the perpetual cycle of birth, life, death and rebirth. The word samsara is derived from Sanskrit and Pāli, and translates to “continuous movement,” “continuous flowing” or “wandering” (Laumakis, 89). The term is used to describe existence in the material world as it is caused by one’s karma. In Buddhist tradition, the state of samsara is characterized by suffering, and is typically described as “the wheel of suffering” or “wheel of life” (“Samsara”, New World Encyclopedia). Samsara is often studied in conjunction with nirvana, the state or realm of peace that exists beyond suffering, ignorance, and rebirth. Liberation from this state of suffering is achieved through following the eightfold path towards enlightenment.

Wheel of life (or wheel of existence), illustrating the six ancient cyclic realms of reincarnation through samsara in Buddhist cosmology. [The Wheel of Life, Mongolia, 1800-1899, Ground Mineral Pigment on Cotton, Rubin Museum of Art, New York City, Himalayan Art. org.]

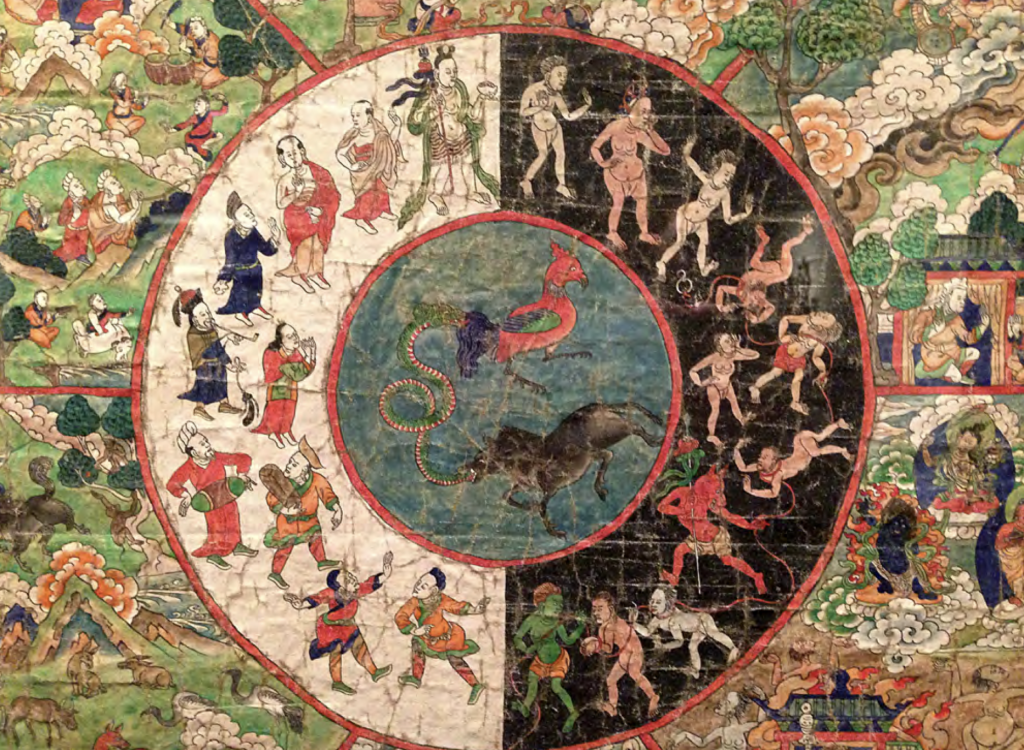

Detail of inner circle of the Wheel of Life, which depicts good karma on the left white half moving upwards in the circle of existence, and bad karma on the right black half, those having performed bad actions moving downward. [The Wheel of Life, Mongolia, 1800-1899, Ground Mineral Pigment on Cotton, Rubin Museum of Art, New York City, Himalayan Art. org.]

In samsara, beings are continuously reborn into one of six realms of existence: gods, demi-gods, humans, animals, hungry ghosts and hells. They are considered wanderers through this seemingly never ending cycle. These realms are what make up Buddhist cosmology, but they are also psychological states. The animal, ghosts, and hell realms are regarded as places of suffering, whereas the godly realms are places of pure bliss. The human realm lies in between; it is considered the ideal state for the practice of dharma and thus an opportunity to attain liberation from samsara. This is because in the human realm, there is said to be sufficient suffering to cause the desire to escape this suffering. (“Saṃsāra and Rebirth”, Oxford Bibliographies).

Japanese depiction of the hell realm and where the sinful are sent after death due to previous bad merit, and tortured by demons. [http://bit.ly/14U41eu]

Movement through these realms are determined by the quality of one’s actions and intentions in what is known as karma. The notion of karma explains a natural law of cause and effect in which all good actions and intentions cause rebirth in a higher form, and the outcome of one’s negative actions and intentions may lead to rebirth in a lower form. It is this belief which drives samsara. In the Buddhist view, the law of karma should not however imply blame for judgement for beings who are of lower realms because by the logic of samsara and karma, all beings have been moving through samsara, between upper and lower realms. Every being has experienced previous lifetimes of misfortune and good fortune (Strong, 281).

Central to Buddhism and the notion of samsara is the idea of impermanence. It is a habitual and repetitive cycle of birth, death, rebirth, and re-death, where there is no clear beginning or end. For this reason, its never-ending nature makes it unfulfilling and is therefore characterized as suffering.

The notion of suffering is known as “dukkha”. A feeling which is triggered by both physical experiences or mental thoughts concerning one’s self and other beings; physical suffering (Dukkha dukkha) from sickness, disease, and death, as well as psychological anxiety (Viparinama dukkha), disappointments, unsatisfactoriness caused by the impermanent transient nature of life. Dukkha is characterized by a sense of imbalance.

While contemporary critics might argue that this way of viewing life is pessimistic, the Buddha is not implying that life itself is miserable. Rather, the human experience is characterized by both pleasure and pain. According to the Buddhist teaching, the three main factors which are responsible for one’s suffering and continued existence in this cycle of samsara are ignorance (avijja) of the true nature of reality, volitional actions (kamma), and craving (tanha) for wanting more (Sucitto, 35).

In the Buddha’s First Sermon, The Dhammachakkappavattana Sutta, which translates to “Setting the Wheel of Dharma in Motion”, the noble truth of the origin of suffering is the craving which leads to renewed existence. According to the Buddha, samsara does not end at death; Each new birth is unsatisfactory and thus a never ending cycle of continually encountering disappointment and suffering until they are able to achieve nirvana.

As taught in the Buddha’s First Sermon, liberation from samsara can only be achieved by following the eightfold path: right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right meditation. Each of these can be summarized by training in ethics (right speech, right action, right livelihood), training in meditation (right effort, right mindfulness, right meditation), and training in wisdom (right view, right intention). Higher training in these aspects leads to liberation from samsara (Sucitto, 37).

The end of samsara is characterized by the state of nirvana — when all human greed, hatred and delusion finally stop and true liberation is achieved. The Mahayana tradition, however, renounces this suggestion that nirvana is an escape from samsara by claiming that there is no distinction between samsara and nirvana; “samsara is itself nirvana” and is also “neither samsara nor nirvana” (Ueda, 75). The Theravada perspective, however, rejects both of these interpretations and places the realms of Samsara in opposition to Nirvana.

Depiction of Madhyamika philosopher Nagarjuna. [Ground mineral pigment on cotton, Tibet, 1700-1799, Himalayan Art.org.]

Madhyamika philosopher Nagarjuna asserted this dichotomy in the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, in which he teaches that everything lacks inherent existence, and equates samsara to nirvana, considering both “empty” or devoid of essence. Under this principle of emptiness (shunyata), liberation is not achieved through complete abandonment of samsara, and renouncing everyday life, but rather through transforming it at its roots. What this means is an internalization of the empty and non-inherent nature of all phenomena so that all delusions and suffering associated with these forms are eliminated.

The final stage of liberation and nirvana is arhat, a fully awakened person who has escaped samsara (“Saṃsāra and Rebirth”, Oxford Bibliographies).

REFERENCES:

Laumakis, Stephen J. An Introduction to Buddhist Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, 2008, pp. 83-104.

Lopez , Donald S. “Setting the Wheels of Dharma in Motion.” The Norton Anthology of World Religions , edited by Jack Miles, W. W. Norton & Company , 2015, pp. 177–181.

“Samsara.” New World Encyclopedia, . 22 Oct 2019, <//www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Samsara&oldid=1026312>.

“Saṃsāra and Rebirth .” Buddhism , 19 Nov. 2019, www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195393521/obo-9780195393521-0141.xml.

Smith, Brian K. “Saṃsāra.” Encyclopedia of Religion, edited by Lindsay Jones, 2nd ed., vol. 12, Macmillan Reference USA, 2005, pp. 8097-8099. Gale eBooks, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3424502735/GVRL?u=31841&sid=GVRL&xid=afae2375.

Strong, John. Buddhisms: an Introduction. Oneworld Publications, 2015, p. 281.

Sucitto, Ajahn. Turning the Wheel of Truth: Commentary on the Buddha’s First Teaching. Shambhala Publications, 2010, pp. 35-37.

Ueda, Yoshifumi, and Dennis Hirota. “The Mahayana Structure of Shinran’s Thought PART I.” The Eastern Buddhist, vol. 17, no. 1, 1984, pp. 57–78. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44361698.

FURTHER READINGS:

For a more comparative approach which discusses Samsara in the context of western philosophy, psychology, and religion, read: [Ishida, Hoyu. “Nietzsche and Saṃsāra: Suffering and Joy in the Eternal Recurrence.” The Pure Land (Berkeley, Calif.), vol. 15, Dec. 1998, pp. 122–145. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rfh&AN=ATLA0001658356&site=ehost-live&scope=site.]

For more information on the Theravada tradition which views samsara in opposition to nirvana, read: [Boyd, James W. “The Theravāda View of Samsara.” In Buddhist Studies in Honour of Walpola Rahula. Edited by Somaratna Balasooriya, Andre Bareau, and Richard Gombrich, pp. 29–43.]

For more information on what turns the wheel of life that is samsara, read this article .

EXTERNAL LINKS:

For a real-life contemporary perspective on the dissatisfaction with samsara in our material world, watch this video on a series of talks on the 41 prayers to cultivate Bodhicitta.

For a descriptive, virtual tour through the transcendental and material realms of vedic cosmology visit this link.

For a vivid discussion on the mythology and imagery associated with the Six Realms of Existence (Wheel of Samsara) listen to this podcast which also explains its relevance in everyday life.

I thoroughly appreciated the third-person approach you took to this subject. I believe it is easy to get persuaded by a singular literature and argue that very same perspective throughout, however you include numerous approaches to how samsara, nirvana and karma coincide. I particularly liked how you magnified your first image to display the inner circle of the wheel of life, portraying good and bad karma on either side.

You raised two very interesting and pertinent topics in your entry: the idea of impermanence and the Mahayana/Theravada view on whether the progression from samsara to nirvana implied eternal bliss. I felt providing more depth to the former with a more conclusive link to the final line would make the end slightly less abrupt, as it dives straight into the final stage of liberation.

I really enjoyed reading this entry. It was written very clearly and would definitely make sense to someone who was unfamiliar with the term. I liked how you briefly defined all the terms that go along with samsara (karma, the six realms, suffering, etc.). I also found it helpful that you kept a critical viewpoint throughout the entry — it made it feel like a true encyclopedia entry. I know this would be hard with the length constraint, but it might be useful to have a more in-depth look at other perspectives besides that of Nagarjuna. Or perhaps you could lengthen the section about him? I’m not sure what would be best but I think it might be nice for the reader to get a sense of a few real perspectives on the term. Overall really good work 🙂

Awesome

cwcwqq EVWVWE