Overview

A mantra (typically translated from Sanskrit as “spell,” “charm,” or “magic formula”) is a sacred utterance or syllable that is contemplated or recited which is believed to be highly charged and powerful (Coop 1). While mantras are typically uttered, chanted, or contemplated in Sanskrit, they do not necessarily have a semantic meaning and their length varies from a single syllable to a hundred or more syllables (Buswell 988). Mantras are thought to embody spiritual or psychological powers and are particularly important in visualization meditation. A mantra serves to “protect” the mind from mental obstructions and is used as a form of incantation in many traditions (Buswell 988). Mantras are particularly important in Tantric Buddhism but they also appear in Tibetan Buddhism, Zen Buddhism, and other traditional Indic religions such as Hinduism (Coop 1). Mantras are also seen in pop culture; however, the definition of a mantra has been transformed into a meaning completely disconnected from its historical and religious context.

Tantric Buddhism

Tantrism is a tradition that developed across the fringes of Indian civilization that was a critic on ordinary society. It assimilated from different pieces of esoteric religious practices from Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism and other philosophical schools (Coward 44). The rise of Tantric Buddhism was an attempt to keep up with the trends of contemporary religious practice at the time. One of the defining features of Tantric Buddhism is the use of mantras and it is sometimes referred to as Mantrayana (the mantra vehicle) due to the central role mantras play in tantric practice (Buswell 988). While mantras in other traditions served “to link the worshiper with the divine and to define the complex order of the universe, the Tantric mantra aims at the annihilation of all distinctions and the affirmation of the worshipper’s identity with the divine” (Coward 45). In other words, Tantric mantras function to collapse the boundaries between the practitioner, the ritual, and the divine into “one all-encompassing relationship” (Coward 45).

Another essential feature of Tantric Buddhism is that it is a secret tradition that can only be understood through a teacher. As a consequence, Tantric mantras are seen as sacred, “secret” sounds that can only be communicated orally from a teacher to a practitioner. In the tradition, mantras are perceived as palpable entrances into visualization meditations which lead to powerfully transformations within the practitioners body and mind. In Tantric Buddhism, recitation of a particular mantra is traditionally repeated a specific number of times and can be performed simultaneously with the visualization of a mandala. Sthaneshwar Timalsina states that “most tantras address some esoteric states of experience and provide a pathway to acquire these experiences… by activating both the domains of sound and vision through the practice of mantra and mandala simultaneously” (Timalsina 1). Additionally, the tradition views that contemplating mantras can result in the embodiment of a particular deity in a practice of worship called Puja. Deity mantras that are used in Puja generally have five parts and each of those five parts can be assigned to different parts of the body, making the entire body of the Tantric practitioner divine (Timalsina 4).

Tantric Mantras include Bija Mantras (mantras that are only a single syllable).

Examples include: oṃ, aiṃ, hrīṃ, klīṃ, śrīṃ, hsauṃ, shauṃ (Timalsina 7)

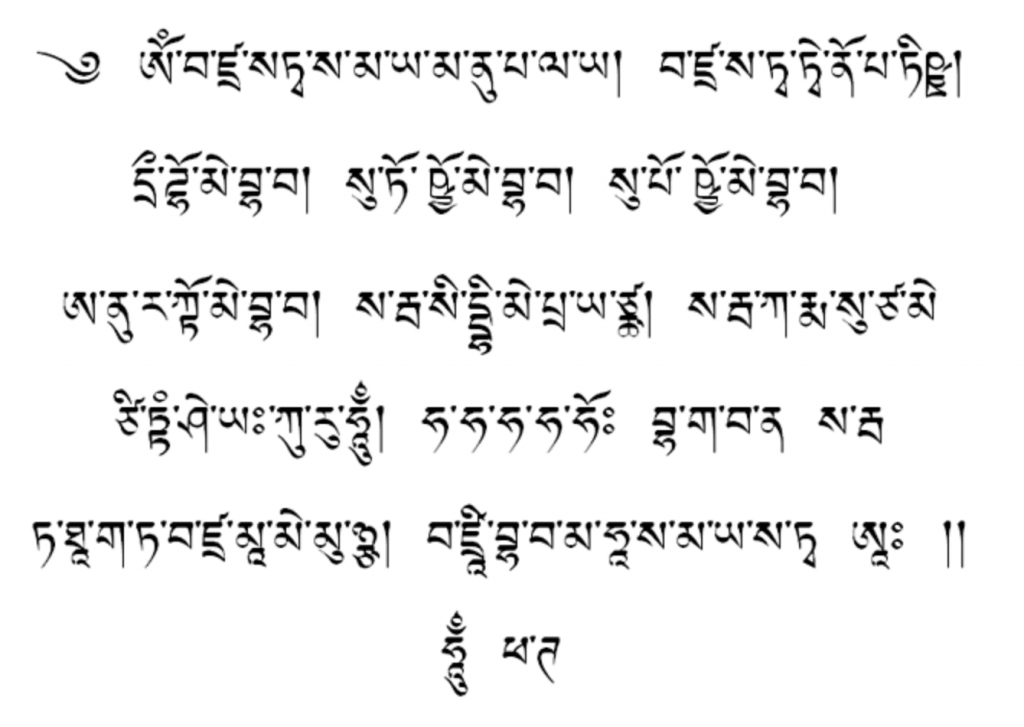

Tantric Mantras are can also be very long, which can be made from multiple seed syllables as well as the name of a particular deity (Timalsina 7). An example of a famous Tantric mantra is the Vajrasattva hundred syllable mantra that is used to purify the mind and body before undertaking Tantric practices (Timalsina 7).

Om Mani Padme Hum – Tibetan Buddhism

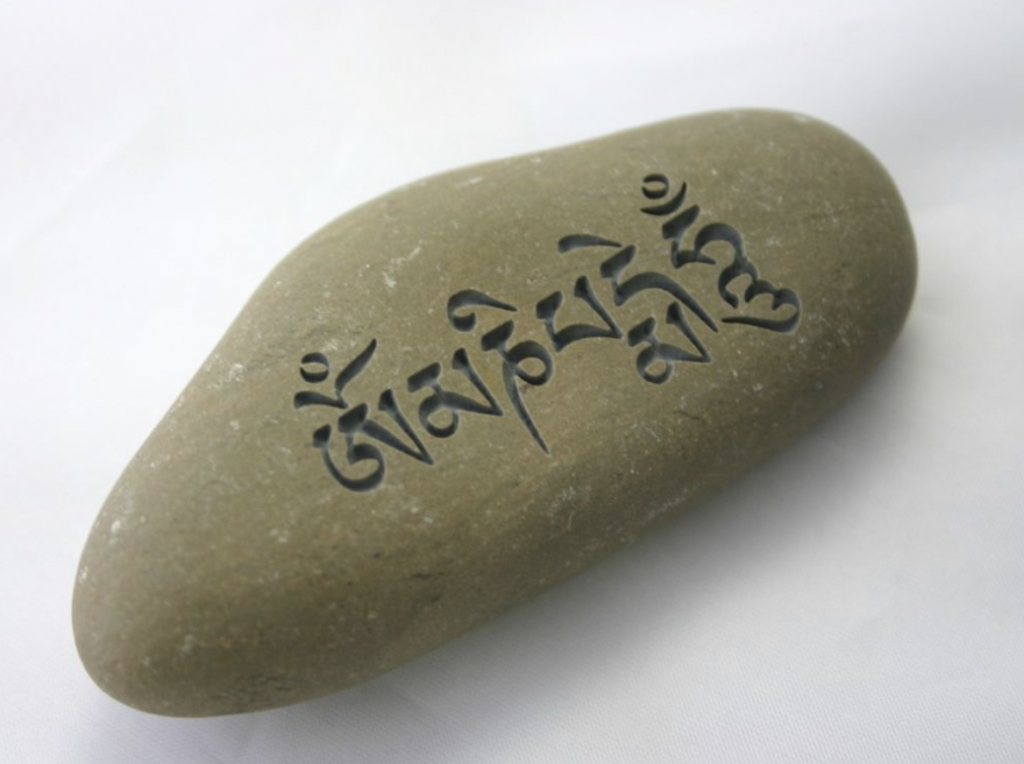

Buddhism, whether from Japan, Ceylon, India, China, Japan, or Tibet, all contain mantras that play a prominent role in the tradition, yet they have different practices and theories associated with them (Alper 295). One of the most prevalent mantras in Tibetan Buddhism is the six syllable mantra Om Mani Padme Hum affiliated with the Bodhisattva of Compassion, Avalokiteśvara (Buswell 988). This mantra is seen carved in stone (known as mani stones) and is also seen on prayer flags or prayer wheels across the Tibetan Buddhist world (Lopez 116). It is believed that the very recitation of the syllables of this mantra holds a transformative power and can manifest a primordial state of mind.

While the mantra Om Mani Padme Hum has held controversy over its true translation, it lacks a full semantic meaning. Taken apart, Om is a sacred syllable in the traditional Indian religions and because it is thought of as “the nature of the five wisdomes” it is the first syllable used (Verhagen 134). Mani is conventionally translated as jewel and padme is typically translated as “lotus,” which represents the lotus flower as well as wisdom (Verhagen 134). Lastly, hum is translated as “take to mind”. Taken altogether, Donald Lopez maintains that the translation of the mantra is “O, you who have the jewel and the lotus” but the true translation is still debated (Lopez 123). Regardless of its translation, most Tibetan Buddhist schools consider the semantics of the mantra as holding less importance than the correlation the six syllables have to other organizations of six in the Buddhist tradition (Lopez 130). Such examples of six include the six realms of transmigration as well as the six negative emotions that need to be resolved in order to reach enlightenment (Gursam 1).

Mani Stone with the Om Mani Padme Hum mantra carved into it. Mani Stones also contain other texts from Buddhism. (12)

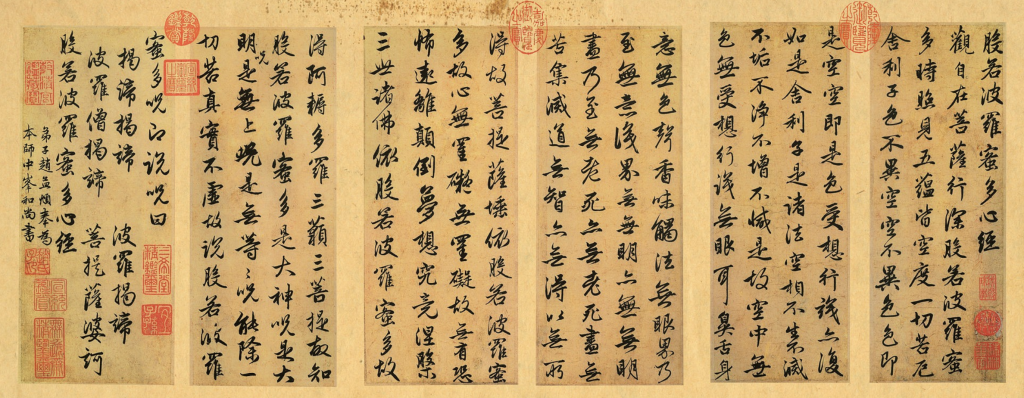

The Heart Sutra

In order to fully grasp the usage of mantras in Buddhism and other Indic traditions, a comprehensive understanding of the Heart Sutra is necessary. The Heart Sutra (The Sutra of the Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom) is notably one of the most fundamental sutras in Mahayana Buddhism and it is apart of the collection of early Mahayana texts known as the Perfection of Wisdom (Prajñāpāramitā). The Heart Sutra is commonly “chanted during ceremonies in China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and Mahayana-associated Buddhist centers in the West, and is an extensively studied text in Tibetan Buddhist schools and in the Shingnon Buddhist school in Japan.” (Gibbon 1). The Heart Sutra is particularly important in the understanding of mantras because while it does conclude with the mantra, “gate gate pāragate pārasaṃgate bodhi svāhā,” the entire text is commonly viewed and chanted like a mantra (Gibbon 6). While the mantra is often translated as “go, go, go beyond, go thoroughly beyond, and establish yourself in enlightenment,” there are other accepted translations of this mantra (Gibbon 3).

Old Origins and Pop Culture

Mantras have served as a foundational practice for Indian society since their origination as their cherished intrinsic power provides a pathway for achieving a closer connection with the divine. As Roger Jackson says, “the notion of sound and syllables as creative realities has been part of Indian thought for millennia, and the notion of a yogin’s participation in a divine world just as old” (Jackson 32). While the root of mantras lies in religions such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and Tantrism, mantras have taken on much different meanings and roles in the modern West as well as contemporary society in the East. In contemporary Western society, mantras are phrases (rarely spoken in Sanskrit) that summarize an individual’s hopes and desires. Mantras are used in chanting circles in Buddhist sanghas as well as during yoga classes and yoga communities in the modern West. Their function in today’s society is far removed from their usage acquired in traditional Indic society as well as modern Indian society. In modern India, mantras are still used in the same way they were used hundreds of years ago, but the way they are represented have slightly shifted in order to keep up with the transforming landscape of modern life. Not surprisingly, mantras still maintain a strong presence in all of the major Indic religions and communities.

Further Readings

- For additional information on the translation of Om Mani Padme Hum as well as the misconceptions of Tibetan Buddhism, click below for Chapter 4 of Donald Lopez’s book. This resource is useful for a more in-depth understanding of the complexity of the translation of mantras. https://it.b-ok2.org/book/2039191/54aeb0

- For deeper knowledge of the Vajrasattva 100 syllable mantra click the link below. It is important in order for a complete perspective on the significance of this mantra in many Buddhist traditions. http://www.visiblemantra.org/vajrasattva.html

- For an eloquent translation of the Heart Sutra done by Thich Nhat Hanh click the link below. This translation is useful because it is a clear and coherent translation. https://plumvillage.org/about/thich-nhat-hanh/letters/thich-nhat-hanh-new-heart-sutra-translation/

External Links

- Click below to listen to Tibetan Buddhists chant Om Mani Padme Hum https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FsbdGcNnQEk

- Click below to listen to Tibetan Monks chant the 100 syllable mantra of Vajrasattva https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sjKbwelO3Lg

- Click below for a journal article discussing the problem of describing mantras as magical. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25484067?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

References

Alper, Harvey P. Mantra. Sri Satguru, 1997.

Braus. “The Core Sutra.” Medium, Braus Blog, 16 June 2018, https://medium.com/braus-blog/the-core-sutra-83e212ef6a65.

“Buddhist Fire Pujas: For Healing and Transformation.” Mindful Tibet, 26 Dec. 2017, http://mindfultibet.com/buddhist-fire-pujas/.

Buswell, Robert E., et al. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press, 2014.

Coop , Paul. “Mantras and Dhāraṇīs.” Mantras and Dhāraṇīs – Buddhism – Oxford Bibliographies, 23 Oct. 2019, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195393521/obo-9780195393521-0102.xml.

Coward, Harold G., and David J. Goa. Mantra: Hearing the Divine in India. Columbia University Press, 1996.

Gibbon , Guy. The Heart Sutra . 14 Jan. 2012, http://mnzencenter.org/pdf/Heart.pdf.

Gursam , Acharya L. “Om Mani Padme Hum .” The Meaning of Om Mani Padme Hum, 30 July 2010, http://www.lamagursam.org/meaning_of_om_mani_padme_hum.html.

Hayes, Richard. “The Mantra at the End of the Heart Sutra.” Heart Mantra, https://www2.kenyon.edu/Depts/Religion/Fac/Adler/Reln260/Heartmantra.htm.

Hayes, Richard. “The Mantra at the End of the Heart Sutra.” Heart Mantra, https://www2.kenyon.edu/Depts/Religion/Fac/Adler/Reln260/Heartmantra.htm.

“Item: Mandala of Avalokiteshvara (Bodhisattva & Buddhist Deity) – Chaturbhuja (4 Hands).” Mandala of Avalokiteshvara (Bodhisattva & Buddhist Deity) – Chaturbhuja (4 Hands) (Himalayan Art), https://www.himalayanart.org/items/279.

Jackson, Roger R. Tantric Treasures Three Collections of Mystical Verse from Buddhist India. Oxford University Press, 2004.

“Mani Stones: One of the Most Popular Forms of Prayer.” Tibetpedia, 19 July 2017, http://tibetpedia.com/lifestyle/mani-stones/).

Lopez, Donald S., Jr. Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998

Timalsina, and Sthaneshwar. “A Cognitive Approach to Tantric Language.” MDPI, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 30 Nov. 2016, https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/7/12/139/htm.

“Vajrasattva.” Vajrasattva Mantra – 100 Syllable Vajrasattva Mantra and Short Vajrasattva Mantra., http://www.visiblemantra.org/vajrasattva.html.

Verhagen , Peter C. The Mantra “Om Mani-Padme Hum” in an Early Tibetan Grammatical Treatise . Edited by Roger Jackson , 2nd ed., The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies , 1990, The Mantra “Om mani-padme hum” in an Early Tibetan Grammatical Treatise

This post has a lot of very good information. The tone is very informative and professional, and the many sections make it easy to focus and understand what you’re reading. I really liked the section on tantric buddhism, and how it is explained that it was developed as a modern take on the religion. There is a bit of confusion in translation however, because at the beginning it is not explained what a mantra is, or how the methods of explaining and detailing it are organized.

I really enjoyed reading your entry on mantras and can tell that this is very well-researched! I was especially drawn to your last section on the origins of mantras vs how mantras are used in Western cultures today. I think it is very important to include this section given that, depending on context, the meaning of mantras has changed greatly and that their use is often “far removed from their usage acquired in traditional Indic society” (such as in a yoga class). One constructive comment I might suggest would be to perhaps make your section on Tibetan Buddhism first (before Tantric Buddhism), as I think this section would make a very nice introduction if you added a sentence or two quickly defining what a mantra is. Otherwise, I think this reads very well and gives a comprehensive presentation of mantras. Great job!